The following is the normal sequence of events that took place when a battery was given a march order.

-

A warning order (W0) would be sent to the battery from the battalion S-3, operations center. This was transmitted using secure-voice radio a day or two before the march order was to take place. The WO would provide the grid-coordinates for the new location, the unit to be supported, and the time the move was to take place.

-

After the WO was received, a reconnaissance of the new location would be arranged. The battery commander would fly to the area and examine the location. If there was a unit already in place, a link-up with the ground element would be made. The terrain and the friendly defensive perimeter dictated where the battery would be placed. Most of the time, the best areas were already occupied and the battery had to do the best it could with what was available.

- As the reconnaissance was being conducted, the battery would start preparing to march order. At least one howitzer always remained in position ready to fire a mission and a skeleton FDC crew was in place to take a call for fire. Everyone else was busy packing, gathering equipment, preparing ammunition, and tearing down bunkers. If the move involved being airlifted off or onto a firebase, then special steps had to be taken to get the gear and equipment prepared for sling loads. If prime movers and other organic vehicles were on hand, then the gear would be prepared to load onto trucks. Things happened in an orderly sequence and every piece of gear had its place. The last thing done was tearing down the bunkers so that the location was not conducive to enemy occupation. This was not to everyone's liking; chances were good that the battery or some other unit would be back. But, it was the prudent thing to do.

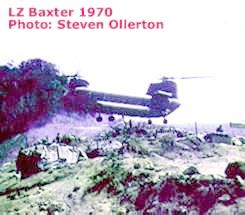

An air move was harder than a road move but most of the battery moves involved a combination of both. Batteries were lifted off remote firebase to a LZ where they would be teamed-up with their prime-movers and cargo trucks so they could convoy to another firing location or to a distant PZ (Pick-up Zone) only to be airlifted again to another remote firebase. It generally took six Crane sorties and 23-25 Hook sorties to move a battery and this would take the better part of the day since there was usually one Crane and 2-3 Hooks involved in a move. Batteries often received march orders to move only two or three howitzers. Such march orders were given to support a special operation or to reinforce units in contact with the enemy. This split the battery for days and even weeks at a time. Those involved in such missions took only the bare essentials and this meant they had to do more with less. This was a trying and draining experience because it meant there would be little rest, lots of action, and few creature comforts.

- On the day of the move, an advance party would leave for the new location. The battery commander, a RTO, a jump FDC, and two to three crewmembers from the gun sections would make up the advance party. The first order of business was to determine coordinates for battery center and to emplace the aiming circle. The jump FDC was contained in a large metal packing crate called a connex. Its inside was modified to accommodate radios, antennas, a power source, chart tables, and all the other necessary gunnery paraphernalia needed to compute fire missions. It could be operational in minutes. Once the aiming circle was set up, the howitzer locations and the rest of the battery area would be marked.

- As the advance party was preparing the new location, the main body was being moved. If it involved an air move, CH 47s (Hooks) would ferry the men, personal gear, building materials, and ammunition. The CH54 (Skycrane) would move the howitzers and

ammo. The advance party would act as a ground control element for the incoming helicopters. This involved maintaining radio contact, marking the locations with smoke grenades, guiding the helicopters into the area, and unhooking sling loads. The helicopter rotors created a powerful downdraft and this flung sand and debris into the air. Gasmasks were often used to protect the eyes and face. A grounding rod made from an entrenching tool would be used to remove the static electricity from the cargo hook. An air move would take the better part of day. On occasion elements of the battery would be left behind because dusk had set in, the weather was bad, or there just were not enough helicopters on hand to complete the move. In those instances, those left behind had to fend for themselves until the next day. ammo. The advance party would act as a ground control element for the incoming helicopters. This involved maintaining radio contact, marking the locations with smoke grenades, guiding the helicopters into the area, and unhooking sling loads. The helicopter rotors created a powerful downdraft and this flung sand and debris into the air. Gasmasks were often used to protect the eyes and face. A grounding rod made from an entrenching tool would be used to remove the static electricity from the cargo hook. An air move would take the better part of day. On occasion elements of the battery would be left behind because dusk had set in, the weather was bad, or there just were not enough helicopters on hand to complete the move. In those instances, those left behind had to fend for themselves until the next day.

Ground moves, on the other hand, were easier to accomplish since the unit moved as an entity. Everything was loaded onto trucks and the convoy normally had 12-15 vehicles spread out over several hundred yards. Convoys always faced the danger of striking a landmine, encountering an ambush, or some other mishap such as impassable roads. When a ground move was being carried out, a fixed-wing aircraft (birddog) would often provide air cover. This was valuable in that the pilot would let the battery commander know how the convoy formation looked, if there were any vehicle breakdowns, and if there were any potential danger areas ahead.

Our 155mm howitzers were much in demand. Their airmobility, variety of ammunition, and ability to deliver rounds capable of piercing jungle canopy or underground bunker complexes made them the weapons of choice. Unit records showed that a firing battery moved between 20-25 times in a year. For the record, here is the list of the major combat units that requested 1/92 fire support: 4th Infantry Division, 1st. Cavalry Division, 173rd Airborne Brigade, 5th Special Forces Group, 11th Ranger Battalion (ARVN), 23rd Ranger Battalion, 1st Parachute Regiment (ARVN), and 3rd Cavalry Squadron (ARVN).

|

ammo. The advance party would act as a ground control element for the incoming helicopters. This involved maintaining radio contact, marking the locations with smoke grenades, guiding the helicopters into the area, and unhooking sling loads. The helicopter rotors created a powerful downdraft and this flung sand and debris into the air. Gasmasks were often used to protect the eyes and face. A grounding rod made from an entrenching tool would be used to remove the static electricity from the cargo hook. An air move would take the better part of day. On occasion elements of the battery would be left behind because dusk had set in, the weather was bad, or there just were not enough helicopters on hand to complete the move. In those instances, those left behind had to fend for themselves until the next day.

ammo. The advance party would act as a ground control element for the incoming helicopters. This involved maintaining radio contact, marking the locations with smoke grenades, guiding the helicopters into the area, and unhooking sling loads. The helicopter rotors created a powerful downdraft and this flung sand and debris into the air. Gasmasks were often used to protect the eyes and face. A grounding rod made from an entrenching tool would be used to remove the static electricity from the cargo hook. An air move would take the better part of day. On occasion elements of the battery would be left behind because dusk had set in, the weather was bad, or there just were not enough helicopters on hand to complete the move. In those instances, those left behind had to fend for themselves until the next day.